Here’s what I didn't know about publishing a book: that the launch, the moment you’ve spent a year (okay, more like three if we’re honest) imagining with a quasi-neurotic intensity (the readings & podcasts & rooftop parties & maybe even an incidental argument with a belligerent reader about the meaning of the word “community”) is going to feel like a wedding you sort of blacked out during, except you’re both the bride and the caterer and at least three of the guests are crying and you are hoping it's because they are moved by something in the book. But who knows.

I should probably clarify that I am the fledgling author in question. This is my debut book, my little party, my mess of internal reactions which, by 7:13 p.m. on the rooftop of a bar named “Visuals” included exhilaration, low-grade nausea, an inability to remember whether I used the Oxford comma consistently, and a kind of soft grief that I didn’t expect.

Let’s begin earlier.

The morning of the launch, I woke up at 5:42 a.m., which is either spiritual or pathetic depending on your relationship with routine. I drank coffee, stared at the ceiling. And drafted and redrafted my launch day post.

After that had been sent out into the algorithm with a prayer and a Hail Mary, I took a little risk and went to Barnes & Noble to see if they had it in stock. Not because I expected some ceremonial unveiling or shrine to my particular corner of emotional maximalism, but because the part of me that still believes in little bits of personal magic needed to see it with my own eyes.

I wandered through the store trying to look nonchalant, like maybe I was just browsing for a birthday card or a coffee table book about moss. And then there it was. A Rebellion of Care. Spine out, in the poetry section. Right there in the world where it did not used to be. Not in my drafts folder. Not a picture on a square with a caption saying “out July 15th.”

But what undid me was realizing the book beside mine was Andrea Gibson’s You Better Be Lightning. Andrea, who had died the day before. Andrea, whose poems had given us permission to write with the full heat of feeling and not apologize for it. Simply because of a quirk of the alphabetical closeness of our last names that I had not considered. To see my book there, still warm from the warehouse, right next to theirs, still vibrating with all the things they taught us about survival and saying it all anyway, it was a lot. I stood there, trying to imagine what it meant to be part of something bigger than a single voice—to be part of the chorus, the echo, an ongoing rebellion of care.

Party time. I arrived to the rooftop bar early, around 4:45 p.m., wearing what I’d convinced myself was a relaxed-but-thoughtful look—blue cotton shirt, dark jeans, and Doc Martens, a small touch in order to feel somewhat myself. I set out the merch table. Emilie arranged the wild flowers that matched the cover. I hovered and stressed. Events unsettle me.

It’s worth noting that a launch party is a weird kind of social experiment: you are simultaneously the object of attention and the facilitator of comfort, both the content and the context. You are expected to be moving around to everyone but also to be still enough to sign books. You are supposed to say something poignant when someone tells you that your poem about grief made them call their mother, but also funny enough that the bartender doesn’t go home grumpy.

By 6:17 pm, there were 82 people on the rooftop. I counted.

By 6:45, there were even more people and most of them were a few glasses in and visibly looser, and definitely nicer to me.

Let me say this plainly: I do not know how to metabolize praise. I understand critique, ambivalence, the slow parsing of meaning. I understand being skeptical of my own motives, even at the moment of moderate success. But I don’t know what to do when someone looks at me and says, “Thank you for writing this. It mattered.” So I say "thank you" back.

Someone else shared with me: “You’ve written a book that’s both a balm and a blade.” That's maybe a better line than anything in the book itself.

Later, in my notes app, semi-drunk on (delicious) wine apertif martinis and with the strange high of being (somewhat) seen, I wrote: “Maybe this is what being known feels like—not the performance of it, but the ache that follows.” I don't have any other use for that line than to give it to you here.

It is 9:04 pm now and the rooftop is thin.

I am sitting alone for a moment. Just me, the last glass, and a book with my name on it that somehow now belongs to everyone else.

A few days later the book was reviewed in the New York Times. That is a kind of honor that carries with it a whole new weight of visibility that I am not yet ready for. But, I guess, I am rarely ready for anything significant. Of course, I’m deeply grateful, not just for the spotlight on the book, but for the generosity of reading, even (especially?) in its skepticism.

I had expected a little snobbiness about Instagram poetry and was not disappointed. But thankfully that wasn't all there was. I appreciated the reviewer’s impulse to soundtrack “Like Every Selfie” with early Talking Heads; those weirdly jubilant dispatches from the brink of alienation felt apt, like hearing a stranger hum your secrets back to you in a different key. I mean, sure, I wasn’t thinking of David Byrne when I wrote the line about praising your friends’ tattoos, but I also wasn’t not thinking about how precarious it feels to love people in public, which is more or less the same thing.

There’s something both sobering and oddly affirming about being situated alongside Rod McKuen and “Influencer Beatitudes” in the same breath—like being told your work is both a warm bath and a suspiciously friendly cult. I take seriously the critique that these poems offer too much agreement, too much light. That they risk becoming fiber without flavor, or worse, motivation without mystery. Some people tire of hope and joy and care more quickly than others.

And yet, what a peculiar and thrilling thing: to see my writing—originally composed in the margins of insomnia, under the glow of the apps designed to eat our attention—now held up to the light of literary scrutiny, as though it were always meant to be there. As though Instagram was just a chrysalis and not, say, the whole bug.

But what struck me most is the reviewer’s search for the cracks, the splinters, the bits where shtick slips and the poems let themselves fail at comfort. That is the work I want to keep doing: not dispensing truth like a Life Coach With Line Breaks™, but opening up space for contradiction, for doubt, for the ugly beautiful stuff we don't usually filter. If there’s any luck or grace in this moment, it’s that the book managed to be both earnest and uneasy enough to provoke that kind of reading. That someone wondered, “Am I supposed to feel this irony, this edge, or did I imagine it?” feels to me not like a flaw in the signal but the beginning of something I like—maybe a conversation, maybe a direction, maybe even a new tone I haven’t found yet. Either way: thank you for listening closely enough to ask.

On the way home from the launch event, someone messaged me to say “I haven’t finished it yet. But I already feel different.”

And I nodded to myself, because I do too.

Let me just say a little something… if you are planning on buying it please do that today. Also, if you know, for sure (FOR SURE) you are going to buy it as a gift for friends, consider doing it today also. Sales have gone well this week and, you know, bestseller lists exist.

You can buy it here or find links to retailers that still have it (apparently a few have sold out and have it on back order) :

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/768719/a-rebellion-of-care-by-david-gate/

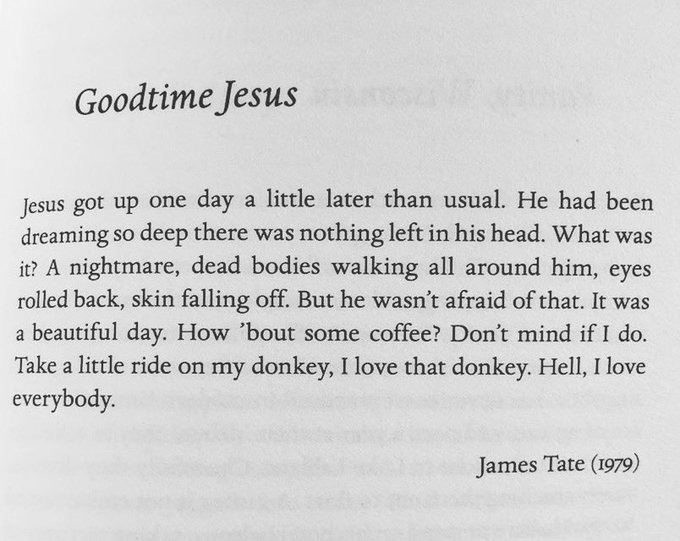

POEM OF THE WEEK: Goodtime Jesus by James Tate

Until next week - Be Excellent To Each Other 🤘 dg

PLAYLIST

Spotify🪀:

Apple Music🍎: https://music.apple.com/us/playlist/take-a-little-ride-on-my-donkey/pl.u-9N9L8XNC76PDaG