WELCOME TO THE BRAIN ROT ERA OF CINEMA

Sound and fury signifying nothing. And that is generous.

There are certain cultural moments that reveal just how far the slow erosion of an artform has come. The wild success of the Minecraft movie is precisely such a moment.

Let us be clear: I have nothing against the game Minecraft. It has sparked the imagination of millions of kids, including all of my own, and provided a pacifier for countless tired parents. The game’s great strength was always its refusal to tell a story. It is a sandbox for creative minds. But that is precisely what makes the movie so culturally ominous to me. It is arriving in a world where IP is king and character and story are optional extras.

This is no ordinary exercise in cash-grab cinema. It is the crowning jewel in a strange new canon of content—a movement we might call, with tragic accuracy, the Gibberish Cinematic Universe (GCU). Its constituents include Minions, Rabbids, Skibidi Toilet, and now, Minecraft. These are not just bad films and TV and content. Bad films we can handle. They are, more troublingly, content without content—sound and fury signifying nothing, and often not even bothering to signify that.

The Minions, of course, were the trailblazers. Originally side characters in Despicable Me, they were never intended to carry a film. Like giving a dog its own TED Talk, the result was inevitable: chaos, nonsense, and inexplicable popularity.

The Minions speak a polyglot stew of incoherent phonetics that is part Esperanto, part Pig Latin and part glossolalia. Their success has led studios to abandon narrative coherence in favor of kinetic visual idiocy. It is slapstick stripped of satire and context.

The Rabbids came next. Ubisoft’s shrieking white rodents began as videogame sidekicks and ended up invading every screen short of a sonogram. Like the Minions, the Rabbids reject all but the most primitive forms of communication: squeals, screeches, and the occasional act of slapstick violence. They are Harpo Marx without the horn or the wit. Language is now optional, and coherence is, at best, a quaint indulgence.

Then there is Skibidi Toilet. For the blessedly uninitiated, this is a viral internet series consisting of humanoid surveillance cameras battling disembodied heads mounted in toilets. The result plays like a fever dream directed by a sentient meme. Its visual grammar is unmoored from all tradition, its narrative arc indistinguishable from psychosis. And yet, it is monstrously popular, devoured by children with the same hunger with which previous generations might have read Treasure Island or Harry Potter.

These are not isolated oddities; they are symptoms of a larger shift. The Minecraft movie is not merely content made for children—it is content made as if by children. Logic, plot, dialogue, and character development are not so much absent as actively shunned. It is not meaningful art, nor is it trash in the traditional sense. It is, what the kids call, brain rot.

There is a line in the movie that is "First we mine, then we craft. Let's Minecraft!". And then they cheer.

It is the natural terminus of the idea: a film based on a property that has no characters, no story, and no point. The game is brilliant precisely because it offers the player freedom to write their own narrative and sense of agency in the world. To impose narrative on it is like imposing grammar on a sneeze.

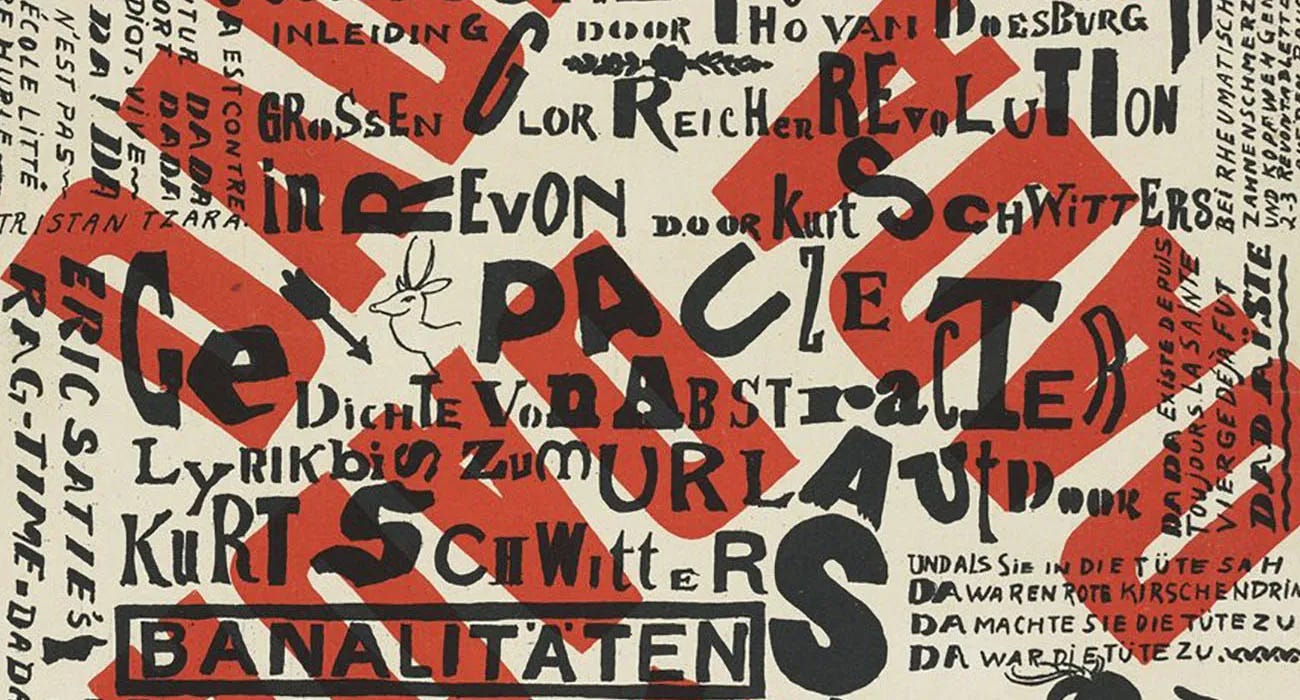

The Gibberish Cinematic Universe has its defenders, of course. They will tell you it is joyful, post-ironic, absurdist fun. They will compare it to Dada or the Theatre of the Absurd. But the GCU has none of Dada’s provocation or existential angst. It is absurdism without hint of intelligence, chaos without critique. Where Beckett gave us silence to reflect on the void, Skibidi Toilet gives us sonic warfare to drown out the very possibility of thought.

I am not snobbish or petty enough to say "this isn't art". But it is certainly low-brow art. And those brows are so low, they would be ripped off during a Brazilian wax.

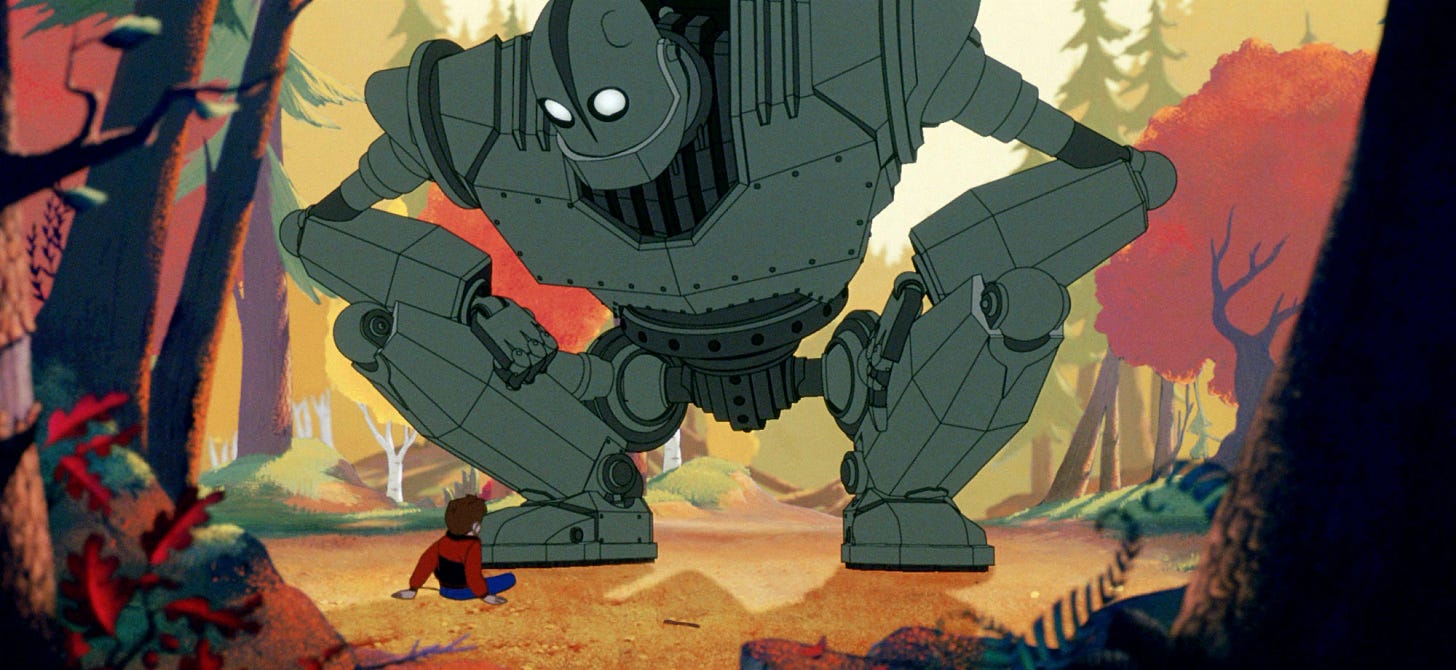

Some may argue that we are simply witnessing the natural evolution of children’s entertainment. But even this is too kind. There was once a time when children’s media - not too long ago - treated its audience as potential adults. Think of The Iron Giant, Spirited Away, or Paddington 2. These films respect the young mind. They assume, rightly, that children can grasp complexity, nuance, and even melancholy. The GCU assumes only one thing: that the audience has the attention span of a goldfish on Adderall.

Indeed, the very structure of GCU content is designed to mimic the sensory overload of TikTok and YouTube Shorts. Scenes are cut before they begin; punchlines arrive before the setup; action happens because stillness might suggest contemplation. It is cinema boiled down to its most basic impulses: bright colours, loud noises, rapid movement. The meme-ification of an artform and the content equivalent of jingling keys in front of a baby.

So where does this road lead? The huge Minecraft box office takings suggest we can expect more. A Roblox movie seems inevitable, followed by Among Us: The Motion Picture—ninety minutes of small men accusing each other of murder in a spaceship, with dialogue cribbed entirely from ChatGPT.

One might reasonably ask: why does it matter? Children have always liked dumb things. We had SpongeBob, after all, and some of us even watched Barney. But even the dumbest kids' shows of the past had a moral center of sorts, a rudimentary sense of story, or at least a lesson in sharing. The GCU offers none of this. Conflict arises not from character or desire but from randomness. Problems are solved not through reason or empathy but through louder gibberish and brighter flashes. It is not that children are being entertained badly. It is that they are being trained not to think at all.